Encounters with the Greatest Library in the World

20 selected stories from The Penguin Classics Book

Samuel Taylor Coleridge was said to have been the last person to have read everything. Nowadays most of us need to be more selective.

The 500 authors who make up the Penguin Classics list span 4,000 years of literary history, and their 1,200 books comprise over 500,000 pages of text.

That means that if you found time to read 50 pages a day, every day of the week, it would take you 27 years to read them all, by which time the list would most likely have expanded further still.

The Penguin Classics Book is intended as a reader’s companion to this most famous of publishing imprints.

It is a book of suggestions and recommendations, drawing connections across the history of world literature, which will hopefully reacquaint you with old friends, introduce you to new titles and suggest ways to map your future reading.

It is also a celebration of an abiding series of books, which began more than seventy years ago and has grown incrementally and idiosyncratically ever since.

Below are selected just 20 titles – from the oldest surviving work of literature to an example of Victorian science fiction – to start your journey among the best books in the world.

‘Definition of a classic: a book everyone is assumed to have read and often thinks they have…’

Alan Bennett

The Beginnings

On chilly nights, amidst the wail of air raid sirens, Emile Victor Rieu stood on the roof of Birkbeck College in central London, scanning the skyline for fires. He passed the time on these long, lonely shifts translating Homer’s Odyssey.

Emile Victor Rieu

‘I went back to Homer, the supreme realist, by way of escape from the unrealities that surrounded us’

E. V. Rieu

Towards the end of the Second World War, with his wife’s encouragement, Rieu submitted his translation to Allen Lane, the founder of Penguin Books.

It was not a promising proposal on the face of it: eight versions of the Odyssey had been published between the wars, including five new translations, of which only two had sold more than 3,000 copies.

Moreover, Rieu was not an established academic. He was a retired publisher of educational textbooks.

In a characteristically impulsive and ultimately shrewd move, however, Lane not only accepted Rieu’s translation, but appointed him general editor of a new series, a ‘Translation Series from the Greek, Roman and other classics’.

Rieu’s Odyssey sold over three million copies. In fact, it was the bestselling of all Penguin books until it was finally overtaken by Lady Chatterley’s Lover in 1960.

‘The King is already familiar with your admirable translation of the Odyssey and looks forward to reading the Iliad’

Note from Buckingham Palace

John Overton was the designer of the first Penguin Classics covers, colour-coded according to language and each featuring a unique, illustrated ‘roundel’.

Penguin Classics colour guide

This look was updated in 1949 by the iconic Art Director Jan Tschichold and, since then, the design has only been updated four times, most recently in 2003.

Within The Penguin Classics Book you will meet every single Penguin Classic in print, and featured below are a few of those books that make up the greatest library in the world.

Emile Victor Rieu

Emile Victor Rieu

Series policy statement from several early Penguin Classics editions

Series policy statement from several early Penguin Classics editions

Penguin Classics colour guide

Penguin Classics colour guide

‘Some books are undeservedly forgotten; none are undeservedly remembered.’

W. H. Auden

The

Ancient World

1. The Epic of Gilgamesh

c. 2100 BCE

The world’s oldest work of literature survives on twelve fragmented, biscuit-brown clay tablets.

This 4,000-year-old story tells how King Gilgamesh of Uruk-the-Sheepfold achieved wisdom through wrestling monsters and embarking on a quest for immortality.

The epic was discovered in 1853, among the ruins of the Royal Library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh, and the tablets now nestle among 130,000 others in the Arched Room of the British Museum in London.

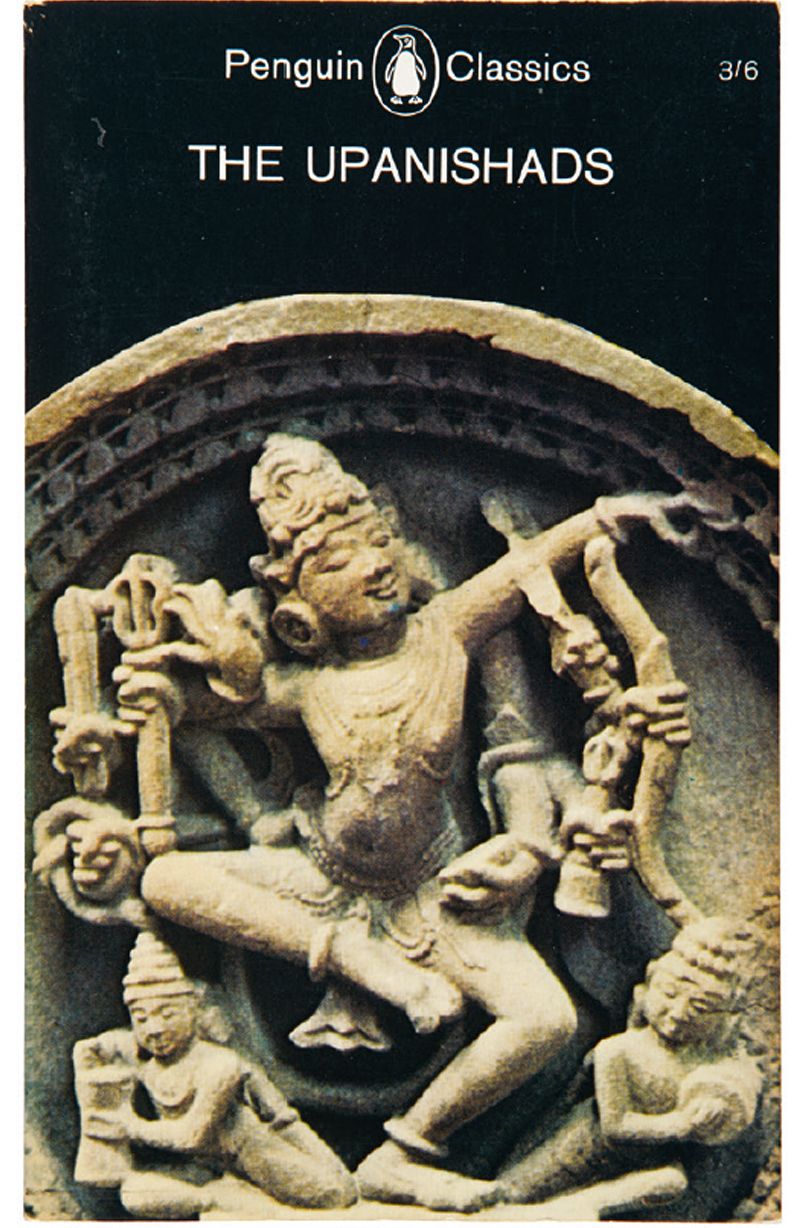

2. The Upanishads

8th – 5th centuries BCE

‘Upanishad’ means ‘sitting down near’. Each Upanishad presents a philosophical discourse with a seated guru, who imparts his esoteric knowledge about the meaning of the world.

The first thirteen or ‘principal’ Upanishads form one of the foundational texts of Hinduism.

Schopenhauer called them ‘the production of the highest human wisdom’.

The translator Juan Mascaró, a Mallorcan linguist who dabbled in occultism before developing a passion for Sanskrit and Pali, describes their spirit as ‘comparable with that of the New Testament’.

3. The Iliad

Homer

c. 750 – 700 BCE

Homer’s identity is mysterious. He may have been a blind minstrel from Ionia, or a Babylonian hostage, or a Sicilian princess (as Robert Graves imagines her in his novel Homer’s Daughter), or ‘Homer’ may be a collective term for an oral storytelling tradition.

No work has had more Penguin Classics translations than the Iliad.

Graves’s 1959 retelling combines darkly humorous prose with lyric poetry, evoking the Iliad’s roots in the bardic tradition and Martin Hammond’s prose translation was acclaimed as ‘the best and most accurate there has ever been’.

The poet Paul Muldoon praised Robert Fagles’s ‘Homeric swagger’ and compared his epic vision of the Iliad to ‘that of film directors like Sergio Leone and Sam Peckinpah.’

4. The Symposium

Plato

c. 375 BCE

Seven men at a drinking party hosted by the tragedian Agathon expound on the nature of love.

They discuss beauty, sacrifice, the difference between sexual gratification and long-term relationships, love as a force of nature and the idea of soul mates.

The playwright Aristophanes is among the company. Socrates asserts that the highest form of love is to transcend the physical and emotional, to become a lover of wisdom, a philosopher.

The Symposium is where the concept of ‘Platonic love’ originates.

5. Meditations

Marcus Aurelius

121 – 180 CE

Marcus Annius Verus was the son of a Roman politician. After his father’s untimely death, however, he was adopted by Aurelius Antoninus, his uncle by marriage, and heir to the Emperor Hadrian.

Marcus changed his name to Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, and when his uncle died in 161 CE, he became emperor himself.

During his military campaigns, Marcus set down a series of self-improving reflections in Greek, which he entitled To Myself.

Known collectively as his Meditations, they form a profound work of Stoic philosophy, with nuggets of sage advice, such as ‘A bitter cucumber? Throw it away’ and ‘The best revenge is not to be like your enemy’.

The

Middle Ages

6. Tales of the Marvellous and News of the Strange

c. 10th century

This remarkable collection of Arabian stories exists in one ragged, incomplete manuscript, discovered in 1933 in a library in Istanbul.

The stories feature monsters, jinn, jewels, living statues, twisted viziers and miraculous apes, with a cast of characters including Julnar of the Sea, Abu Disa the Bird, the White-Footed Gazelle and the Man Whose Lips Had Been Cut Off.

There are libidinous mermaids and psychopathic nymphomaniacs and other raunchy high jinks, not least in the ‘Tale of the Forty Girls and What Happened to Them with the Prince’.

7. The Pillow Book

Sei Shōnagon

994 – 1002

Sei Shōnagon was the daughter of a well-known waka poet, a form that anticipated haiku. She was a gentlewoman at the court of the Empress Consort Teishi.

Her compilation of apparently private anecdotes, observations, lists and poems reveals a rarefied world of poetry, love and fashion, as well as her views on nature, high society and romance.

She relates how a minister presented the empress with a bundle of paper: ‘What do you think we could write on this?’ Her Majesty inquired.

‘They are copying Records of the Historian over at His Majesty’s court.’ ‘This should be a “pillow”, then,’ I suggested. ‘Very well, it’s yours,’ declared Her Majesty.

The empress handed the sheaf to Shōnagon, who kept it by her pillow, and used it to record ‘things I have seen and thought’.

8. The Travels

Marco Polo

1296 – 9

Marco Polo was the son of a Venetian merchant. In 1271, the 17-year-old Marco accompanied his father on a 24-year journey to the Far East.

His description of the World was Europe’s first eyewitness account of the Far East and it was exceptionally popular.

It is a mixture of practical gazetteer and medieval romance, combining itineraries with colourful cultural observations and fantastical stories, from the spice forests of Sumatra to the Sea of Japan.

It is populated with vast cities, pearl fishers, ‘paper money’ and naked warriors, and inspired Christopher Columbus, two centuries later, to seek a shortcut to these fantastical lands.

‘I am glad to learn from Dr. Rieu that you are prepared to entrust me with the job of turning Polo’s Description of the World into a Penguin Classic,’ wrote R. E. Latham in 1953.

‘Perhaps I should warn you that it will be a very fat Penguin and will probably have to be twins.’

‘We like our Penguins fat nowadays,’

replied A. S. B. Glover, Penguin’s general editor.

9. Sunjata

Gambian Versions of the Mande Epic

c. 13th century

In the early 13th-century, there was a slow-witted, greedy child among the Malinké people of what is now eastern Guinea.

He was called Sunjata Keita and, although he was the son of a hunchbacked, buffalo-woman, he grew up to be a mighty warrior with superhuman strength.

With the aid of his sister, Sunjata crushed the Susu overlords and founded the Mali Empire, which lasted for four centuries.

Sunjata’s story is still celebrated in West Africa as part of a vibrant oral tradition. This volume presents two versions of the myth, translated from live performances that were recorded in the early 1970s.

Bamba Suso’s version centres on the human and familial relationships in the story; Banna Kanute revels in the story’s violence and magic.

10. The Book Of Margery Kempe

1438

Margery Kempe was a merchant’s wife who suffered from post-natal depression.

She experienced visions of violent demons with flaming mouths, urging her to renounce Christianity and take her own life, until the handsome figure of Christ appeared, sitting on the edge of her bed.

Years later, after bearing fourteen children, she persuaded her husband to join her in a mutual vow of chastity and she set off on an adventurous life of pilgrimage, visiting clerics, mystics and recluses around England, Europe and the Holy Land.

Her book is the first autobiography in the English language. It describes her extensive travels and extraordinary, time-travelling visions: she was present at both the Nativity and the Crucifixion, for example.

Her devotions took the form of loud public wailing with copious tears, and she was tried several times on charges of heresy.

The manuscript was discovered in 1934, in a house in Lancashire.

Early

Modern Europe

11. Don Quixote

Cervantes

1605 – 1615

The modern European novel was born at the beginning of the 17th century with the publication of Don Quixote.

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra was the son of a barber-surgeon. He fought at the Battle of Lepanto, was captured by Barbary pirates, became an Algerian slave and spent several stints in prison.

He is considered the greatest writer in the Spanish language.

Don Quixote is ostensibly a satire on ‘books of chivalry’: a country gentleman becomes so immersed in romantic tales of knight-errantry that he embarks on his own preposterous adventures, riding his old nag Rocinante, recruiting the simple farmer Sancho Panza as his squire and famously ‘tilting at windmills’, believing them to be giants with vast flailing arms.

But this great book is also a tapestry of multiple plot strands and stories within stories, raising questions about the nature of reality and the implications of reading.

12. Leviathan

Thomas Hobbes

1651

After graduating from Oxford, Hobbes became the tutor to the Cavendish family of Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire and lived with them for much of his life.

He devoted his scholarly attention to devising a ‘political science’, the culmination of which was Leviathan, written during the English Civil War.

It formulates a science of morality and offers a rational basis for legitimate government.

Hobbes begins by postulating a pessimistic ‘state of nature’, imagining the anarchy that would prevail if humans had no system of government at all: he describes the natural life of man as ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short’.

From there he develops the notion of a necessary social contract between the people (the ‘Common-wealth’) and the central authority (the ‘Leviathan’).

This powerful idea has formed the basis of most subsequent political philosophy.

At the time, however, the implication that mankind is fundamentally self-serving was considered appalling, and copies were burned publicly by the University of Oxford on the charge of sedition.

13. The Female Quixote

Charlotte Lennox

1752

Lennox was born in Gibraltar and brought up in New York. On her arrival in England, she entered literary society and received the patronage of Samuel Johnson and Samuel Richardson.

Lennox’s playful novel inverts Don Quixote. The sheltered protagonist, Arabella, reads so many French romances, she expects her life to be equally full of romantic adventure.

She confidently slays lovers with smouldering looks, mistakes a transvestite prostitute for a gentlewoman in distress and cheerfully throws herself into the Thames to escape a group of ‘ravishers’.

The Female Quixote was one of the inspirations behind Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey.

14. Candide, or Optimism

Voltaire

1759

François-Marie Arouet wrote a staggering quantity of books and letters under the nom de plume ‘Voltaire’.

After spending time in the Bastille for writing satirical verses, he embarked on a self-imposed exile around Europe, staying in England and the French countryside, at the Prussian court of Frederick the Great and finally near Geneva.

He was one of the most influential figures of the Enlightenment period.

In what John Updike described as the ‘prince of philosophical novels’, the ingenuous Candide is raised in the German castle of Baron von Thunder-ten-tronckh and tutored in metaphysico-theologico-cosmo-nigology by Dr. Pangloss, who inculcates him with the optimistic philosophy that ours is the ‘best of all possible worlds’.

Candide finds his optimism tested, however, by the rape, pillage, flaying, earthquakes, syphilis, murder and other misfortunes he encounters on his travels.

He finally retires to a small farmstead and adopts a more pragmatic view of life: ‘we must cultivate our garden,’ he says.

15. The Interesting Narrative and Other Writings

Olaudah Equiano

1789 – 94

Equiano was born in what is now southeastern Nigeria, enslaved at the age of eleven and transported to the West Indies. He was brought to England by a British naval officer, who renamed him Gustavus Vassa.

He eventually bought his own freedom, travelled the world and returned to London where he married an Englishwoman and became a prominent social reformer.

His ‘interesting narrative’ depicts the horrors of slavery in Africa and the West Indies. It is both a sobering autobiography and a passionate literary treatise on religion, politics and economics.

It was an instant success and contributed to the passing of the the Slave Trade Act of 1807, which abolished the slave trade in the British Empire.

The

Industrial Age

16. Faust

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

1808, 1832

Known as Das Drama der Deutschen (‘the drama of the Germans’), this two-part verse tragedy is considered Goethe’s magnum opus and perhaps the greatest work of German literature.

Based on the medieval myth revisited by Christopher Marlowe, the devil Mephistopheles, initially disguised as a poodle, offers to grant Dr. Faust’s every earthly wish, in exchange for his everlasting soul.

In Part One, Faust strikes the deal and woos the lovely Gretchen; in Part Two, he scales the heights of politics and power and summons the beautiful Helen of Troy back from the dead, his arrogance and self-delusion leading inexorably towards destruction.

Goethe finished Part Two in the year of his own death.

The Serbian electrical engineer Nikola Tesla was obsessed with Faust. He learned it off by heart and was reciting it when he had an epiphany, which led to his idea of a rotating magnetic field and ultimately his invention of alternating current.

17. Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus

Mary Shelley

1818 – 31

Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin was the daughter of the radical writers Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin, but she never knew her mother, who died when she was ten days old.

In 1814, she eloped to Europe with Percy Bysshe Shelley and they married in 1816.

Mary and Percy spent the stormy summer of 1816 on the shores of Lake Geneva with Lord Byron and his friend John Polidori.

Byron suggested a ghost story competition and Mary, 18 years old at the time, based her contribution on a terrifying waking dream:

I saw the pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together. I saw the hideous phantasm of a man stretched out, and then, on the working of some powerful engine, show signs of life, and stir with an uneasy, half vital motion.

She worked her short story into her famous novel, which she first published anonymously in 1818.

It has become the archetypal modern myth, portraying the hubris of humanity and the maker’s rejection of his own creation.

18. Jane Eyre

Charlotte Brontë

1847

Charlotte Brontë grew up in Haworth parsonage, on the edge of the Yorkshire moors.

After her mother and two older sisters died, she was educated at home with her three surviving siblings, Emily, Branwell and Anne.

She later became a teacher and a governess and encouraged her sisters to contribute to a joint poetry collection, published under the pen names ‘Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell’.

Her three siblings died between September 1848 and May 1849.

Jane Eyre is the story of an independent-spirited but lonely governess who falls in love with her Byronic employer, Mr. Rochester, only to uncover a dreadful secret.

Brontë blends the interiority of Romantic poetry with a dramatic, Gothic plot to create one of the first subjectively psychological novels.

19. News from Nowhere and Other Writings

William Morris

1856 – 96

Morris was a wallpaper designer, furniture craftsman, embroiderer, poet, translator of Icelandic sagas, businessman, socialist, conservationist and publisher.

William Guest, the narrator of News from Nowhere, is swimming in the Thames after a meeting of the Socialist League, when he notices that the ‘soapworks with their smoke-vomiting chimneys’ are gone and Hammersmith Bridge has been transformed into a dream structure with ‘gilded vanes and spirelets’.

He has woken into a socialist utopia, an agrarian society with no private property, no authority, no money and no class system: he takes a boat trip up the Thames to explore this perfect, future world.

20. Flatland

Edwin A. Abbott

1884

Narrated by A. Square, Flatland begins as a description of the two-dimensional Flatland, a thinly disguised satire of Victorian society.

Part Two describes Square’s vision of one-dimensional Lineland, the miraculous visit of A. Sphere from three-dimensional Spaceland, and Square’s revelation that there may be other lands, with four, five, six or more dimensions.

The novella has been described as a premonition of the fourth dimension in Einstein’s general theory of relativity.

Edwin Abbott Abbott became headmaster of the City of London School, his alma mater, at the age of just 26, and remained there until his retirement.

He taught the future Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, and introduced many new subjects to the school’s curriculum, including comparative philology, chemistry and English literature.

The Penguin Classics Book

A reader's companion to the largest library of classic literature in the world

“A classic [...] survives because it is a source of pleasure and because the passionate few can no more neglect it than the bee can neglect the flower.”

Arnold Bennett